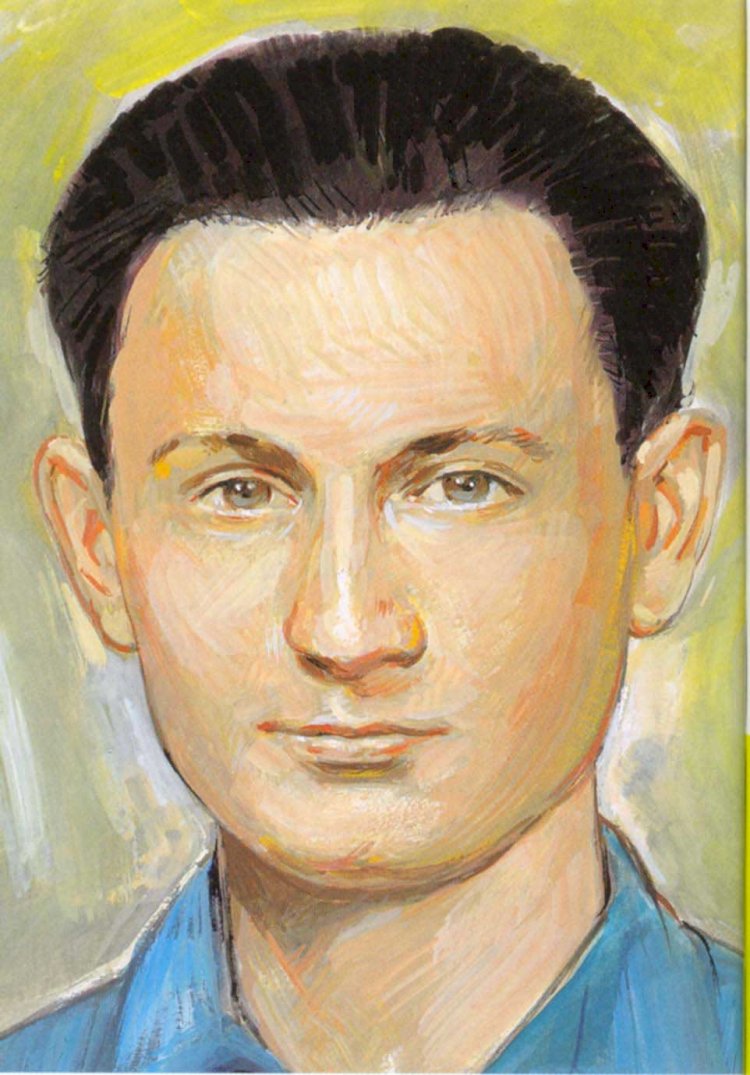

Stephen Sandor – Salesian Brother, Martyr

A 10-page biography - Br Stephens standing behind his parents and his two brothers on the left

1914 was a tragic year for Europe. On July 28, after the assassination attempt in Sarajevo, Austria declared war against the Kingdom of Serbia. And thus began the great massacre of the First World War. Towards the end of the preceding year, on November 6, 1913, the first Salesians – a group of Hungarian youth who had done their formation in Italy – had arrived in Hungary, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

It was into this context that Stephen Sandor was born on October 26, 1914, in the town of Szolnok, situated some 100 kilometres to the southeast of the capital, Budapest, on the Great Hungarian Plain. Cutting through the town is the Tibisco River, an important feeder stream of the Danube, which begins to become navigable precisely in Szolnok. Its founding dates back to the early times of the occupation of the Carpazi Basin by the Magyar tribe. The river and the fertile and extensive plain which begins at the foot of the Bukk Mountains, have always favoured trade, making the town a lively centre of commerce and culture. Given its geographic position it became an important junction for communication, especially for train routes. The presence of thermal springs and the long periods of sunlight contributed to its touristic and agricultural development, in addition to the presence of paper mills and railway offices.

Childhood and Youth

Stephen was the firstborn of three brothers. Three days after his birth he was baptized in the Franciscan parish, which would later play a significant role in the Christian formation of the boy. His father, who by family tradition had given his own name to his son, was a railway man. Such stable employment (then, as today, not taken for granted) allowed his family to live a modest and tranquil lifestyle at a very difficult moment for the Magyar nation. Given the strategic importance of the railways in wartime, Stephen’s father was not sent to the front; he was thus able to be part of his children’s upbringing firsthand. He exerted a very positive influence on his sons, and was able to provide for their education in a dignified manner.

From the time he was a small boy Stephen was regular in going to his parish. The Franciscan community to whom the church was entrusted, were a bulwark of Christian life in the town. As an altar boy, Stephen carried out his service with joy. Later, this passion for acts of worship would re-emerge when, as a Salesian Brother, he would train a group of exemplary altar boys in school and at the oratory, with much seriousness of purpose. For him, already in the days of his youth, it was not simply a matter of external, ritualistic, ceremonial activity, but a true form of service to the Lord, the expression of an authentic love for the Eucharistic Jesus.

His membership of the “Szìvgàrda” (literally, the Guards of the Heart), was a true and proper initiation into a Catholic Association. It promoted groups of boys and girls who did community and educational activities inspired by devotion to the Sacred Heart. The organization was active from 1920 to 1948 when the Communist regime eliminated all Catholic Associations.

He was a boy who was always happy and even-tempered, who loved to play and who never sat still: this is how his companions remembered him. Well-loved by all, he had the temperament of a leader; he gathered around himself children of his own age and knew how to guide them without yearning for power and without bullying. He enjoyed acting in plays and showing off on stage so as to entertain his friends. He preferred to be the referee so as to give the little ones the chance to play.

Even at home he looked after his little brothers and was the one to lead prayers before meals and in the evening. He always helped his mother with the household chores. When his younger brothers were guilty of some mischief it was natural for him to take responsibility for it himself.

As a teenager, he often went to the local Franciscan community, becoming a friend of the Brothers Minor, in particular of one of them, a Fr Casmir Kollàr, who was his spiritual director. This was not a common thing for a young boy; his openness with this worthy priest accompanied him along a constant spiritual growth, even in difficult situations. In fact, in the post-war years unemployment was great; there were, even then, times of grave economic crisis; the result was that it was difficult to find a stable job. After finishing the obligatory years of schooling, young Stephen had to undertake very demanding physical labour such as carrying sacks of cement in the paper mills or working in a copper foundry. He was the shortest of his brothers and of weak physical constitution. He worked with dedication and every evening his mother used to care for the wounds on his shoulders which came from carrying the heavy loads. This she did according to the home remedy: smearing them with pig fat.

In Don Bosco’s footsteps

When the Franciscans saw the seriousness of his commitment and his great common sense, along with the quality of the Christian life he lived, they counseled his family to send the young boy to the Salesian school, “Clarisseum” in Ràkospalota (at the time a large suburb on the outskirts of Budapest). Just a short while before, on some land received from a noble family, the Salesians had opened a Graphic Arts trade school and a weekend oratory for poor boys, ages 10 to 17, including orphans or boys in trouble, sent by the Ministry of Justice. This was a novelty in Hungary at the time. Notwithstanding the great effort he put into his studies, Stephen never attained high marks; still, in June of 1928, he completed the curriculum with a sufficient average.

At this point, after returning home, the 14-year-old was directed to become an apprentice metallurgist (a lathe turner, one who casts molten copper); there was no other possibility for him given the difficulties that existed when trying to find work in those days. During this entire period he was constantly in contact with the Franciscans and, in particular, with his regular confessor. This consistent concern for his spiritual life, along with the profound impression that his time at Ràkospalota had left on him, brought him to reflect on what God wanted of him. And thus he recognized in himself, with the help of his spiritual guide, the signs of a call from God to the Salesian religious life. As he would later say, reading the Salesian publications had impressed him and made him reflect. Even in this trait you can see the motivation for his choice: his bent for typographical work and his love for the press and for spreading the Word among the common people. From a letter written by his Franciscan confessor and spiritual director, we learn that in 1932 at the age of 18, he had presented a request that wasn’t accepted because his parents didn’t give their consent. Meanwhile, he did different types of work, putting all his effort into them, even as a simple day labourer in railway maintenance. His capacity for adaptation to different types of manual work was notable, as was the case even during Don Bosco’s youth. During this time he continued his correspondence with the “Clarisseum.” So as not to upset his parents, the replies went to the Franciscan monastery.

When he reached the age of 21, at the end of 1935, Stephen sent his formal request to the Salesian Superior, Fr Jànos Antal. Among other things, he wrote: “I feel the call to enter the Salesian Congregation. There’s a need for work everywhere; without work, one can’t reach eternity. I like to work.” This underlines a fundamental element of his life: he felt that the world of work was his. He was accepted as an aspirant-candidate to Salesian life.

On February 12, 1936 he returned to the “Clarisseum” for his trial period. Living in that community, he worked with enthusiasm as an assistant typographer, as a sacristan, and in the oratory. After three months, he asked to enter the Novitiate but the Superiors felt that it was better if he first completed his formation as an aspirant, as well as his technical preparation as a printer. Notwithstanding that for those times his age was a bit above the average for Novices, he continued his work until the end of March 1938, when, at the age of 24, no longer an apprentice, but an already accomplished typographer, he asked to enter the Novitiate.

A Rocky and Steep Road in the Novitiate

But in 1938, Hungary was going through interesting times: the re-annexation of the Magyar territory, split off in the Treaty of Trianon (1919) and now re-assigned to the Hungarian government in the treaties restructuring Central Europe in 1938. And so Stephen, after having begun his Novitiate in a regular way, on April 1st of that year had to break it to do military service. As a soldier, he continued to uphold his high tenor of spiritual life and apostolate, staying in touch by letter with the Superiors of the Novitiate. He spent his leave at the “Clarisseum” and handed over to the Provincial the little money he had received.

After his discharge in 1939 he began his Novitiate again on April 30. At 25 years of age he was much older than his Novitiate companions who were little more than teenagers. The admiration that his behaviour aroused in his young companions can therefore be well understood. “Even if he was 9 or 10 years older than we, he shared our life totally, in an exemplary fashion. We didn’t feel this age difference at all. Stephen was learning the trade of typography, but in the Novitiate he was unable to practise it; he carried out his chores well, above all in the kitchen. His gift as an educator was apparent even to us novices, especially in community activities. With his personal appeal, he enthused us to such a point that we took for granted that he could tackle with ease even the most difficult tasks.” He gave the impression that he was praying almost continually. At the same time, he made a name for himself in our group for his capacity to attract even the most skeptical companions, provoking an enthusiastic reaction in them, above all when the amateur theater group had to present some comic scenes.” “His spiritual level was a great deal superior to that of the others.” These are the sworn testimonies of his old novitiate companions.

The economic circumstances of the years 1939-1940 were very serious. With the occupation of Poland, World War II began. But the novitiate at Mezonyàràd was able to count on its large property which guaranteed a good supply of foodstuffs.

Stephen finished his novitiate with the First Profession of his Religious Vows, as a lay Salesian (a “coadjutor Brother”) on September 8, 1940. From his correspondence in this era, you can see his great joy and enthusiasm for that life. He returned to the “Clarisseum,” to his work in the print shop, now as one of those in charge, and to the animation of the public church annexed to the oratory. The print shop, Don Bosco Publishers, enjoyed great national prestige. Besides Salesian publications (the Salesian Bulletin, Missionary Youth…) it also published precious series of theatrical works for the young, books of spirituality for the young, and religious instruction books for the common people.

It was during these years in Hungary that the Young Catholic Workers (‘KIOE’ in Hungary) came into being under the patronage of Don Bosco. At the “Clarisseum” Stephen was the promoter and the soul of this organization. His group became the model for other groups; he instilled a calm atmosphere and the sacramental and educational spirituality typical of Don Bosco. Discussions on the catechism, apologetic conferences, Adoration, excursions and pilgrimages, sports and games, holy joy characterized the life of the group. The young were attracted to it and did not abandon this work, even when their leader was recalled to arms. Hungary had entered the war on the side of Germany, June 22, 1941.

On the War Front

Sandor did his military service as a telegrapher, rank of Corporal. Some of his soldier friends testify that he did not hide that he was a consecrated Religious from his unit. He created a little group of soldiers around himself, attracted by his example, whom he encouraged to pray and avoid using blasphemies. Up until 1944, with short breaks, he remained in the army. During this period, inasmuch as it was possible, he kept in constant contact with his Religious Superiors, in particular with Fr Jànos Antal, Provincial. From his letters it is clear that he was concerned about his spiritual life, even if he found himself in grave situations. In his brief periods of furlough he immediately returned to his Salesian house, which he felt to be his true family and was always welcomed with great affection. He was then transferred to the Russian Front where he took part in the most difficult battles. He was awarded the Cross of Merit for valour. He took part in the disastrous retreat from Don Bay. Made a prisoner of war in Germany by the Americans, he was able to return to his country within a short time.

In 1944, he took up his work again at Ràkospalota, inasmuch as the dramatic circumstances permitted. On February 13, 1945, after long and bitter battles lasting three months which resulted in the destruction of the residential area, the entire city of Budapest was under the control of the Soviet army. In this time, the Salesians remaining in the city suffered terribly from hunger, unable to work, and because of requisitions on the part of the occupiers. At Ràkospalota, emptied of its students, beds and mattresses were sequestered. The confreres had to find themselves places to sleep, among the ruins, facing a particularly severe winter.

The Shadow of Persecution

On April 3, 1945, the apostolic nuncio, Archbishop Angelo Rotta, who had worked so much to save many Jews from deportation, was expelled from his country by the personal order of Marshall Vorosilov.

The Salesian work was reduced to a few oratory gatherings, disturbed by the nascent communist organizations which sought to strip away even those few youth who had contact with Religious.

On August 16, 1945, the President of the Provisory Hungarian Government signed the first decree of reform of the national school system without consulting the Church, which had a large percentage (43%) of the schools which would be affected by the reform. In autumn, the attacks against religious schools began: revision, in a Marxist sense, of all of school texts and many Catholic texts were simply prohibited. The Hungarian Salesian Superior told the General Council in Turin: “… Now we publish neither the Salesian Bulletin nor the Missionary Youth. The laws in force impose upon us the greatest economy of paper.”This last initiative was a way the Regime controlled the press: they needed to have specific permission to acquire paper.

The first post-war elections were held On November 4, 1945: the Communist party gained only 17% of the vote but with the support of the occupying Soviet army, it controlled the entire political apparatus. The “Don Bosco” Press at Ràkospalota was under surveillance by the Communists. They could not print books and even the bookstore didn’t sell the remaining stock “because the people spend their money only on bread.” Catholic press was authorized for only two weekly publications which, however, due to the lack of paper, only came out a few times.

On May 2, 1946 the Superior of the Salesians in Hungary wrote: “At Ràkospalota we are up in the air. The owners of the house want to send us away from the Institute. We are losing what few rights we have. We hope to be able to get out of it… .”

In July 12 to 27, 1946 the Communist Minister of the Interior, Rajk Làszlò, dissolved all religious associations, youth and adult. Only pious associations were permitted, with restrictions. Many heads of the dissolved associations were imprisoned. At Ràkospalota the groups led by the Salesians were also affected. In a particular way Stephen suffered when the KIOE, of which he had become one of the leaders, was banned. Notwithstanding the legal prohibitions, however, he continued this activity in a quasi-clandestine way, to avoid exposing himself or his students to the scrutiny of the political police. They changed their meeting place every time, making them look like country outings of little groups of youth, or like they were getting together for a party in the evening. In 1948 he was leading six active youth groups, among which were several past pupils of our school. The topics of their meetings had absolutely nothing political about them. They were solid religious instruction so as to give the young the foundation of their Faith in such a way as to be able to resist the atheistic propaganda. They prayed a lot. He wrote some appropriate prayers expressly for them.

The writings from those years which were able to reach his Superiors speak of serious lack of food and heating in the coldest winters; on account of this, his health was weakened. The consequences of these privations from war and the post-war period were obvious.The work in the print shop at Ràkospalota was reduced to next-to-nothing. Still, in April 1948 he succeeded in printing a few copies of the “Preventive System” by Fr Bartolomeo Fascie, a Salesian classic translated into Hungarian. But already in July, his Hungarian Superior communicated with the Superiors in Rome that “the print shop is just about paralyzed. The Censor gives us permission each month to print at most one item.”

On June 16, 1948, the Hungarian Parliament decreed the nationalization of all schools by a vote of 230 for and 63 against. The Hungarian Episcopal Conference reacted by establishing that Priests and Religious should not accept teaching or administrative posts in nationalized schools, except for the teaching of religion. The Hungarian Salesians thus saw the regime take over their network of schools and a dozen other places for poor children connected with the schools (boarding schools). All they had was the pastoral work in the churches and the teaching of religion in state schools. But even this, a year later, on September 6, 1949, became optional and was accompanied by every kind of pressure on parents not to send their children to religion class. The parents who were doing so had files kept on them, lost their work, and their children could not attend university…

With the school at Ràkospalota nationalized, the print shop remained in Salesian hands but under serious limitation and without outside personnel. Stephen kept the machines in good repair and dedicated as much time as possible to following up young people outside the house, nourishing their Christian life by his example and with activities. The Salesians, in fact, had received permission from the Bishop to continue, where possible, their educational work in places that had previously received their students from the State (principally from the Ministry for Justice). There was a sizable number of these. They had been leaders in this field, even in the wider European. Back in 1925 the juvenile correction centre at Esztergomtàbor had been entrusted to them. The Bishop of Vàc, on whom Ràkospalota depended, set up a public church there which he gave to the Salesians, making the permanence of the Religious Community easier, even if reduced in number. Stephen was able to continue to occupy himself with the altar boys and with those few children who attended the parish, besides continuing his work as sacristan – which he loved doing and carried out with a great spirit of piety and to the edification of the priests themselves.

At the end of December 1948, it was hinted to the Salesians at Ràkospalota that they should leave the building. An appeal was turned down. Thus, the print shop languished as they did not receive permission to print anything other than some leaflets of an administrative type, but nothing that had religious content. Finally, in the summer of 1949, it was confiscated by the State. Thus, after 23 years of activity, all income for the Salesians ceased and it became very difficult to finance new candidates to Salesian life. The publishing house, in fact, had been an important source of income for the young confreres: at Szentkereszt there were nineteen Theology students, at Mezonyarad thirty-one Philosophy students, and at Tanakajd eight novices to support. It is easy to imagine the pain that Stephen felt seeing the cessation of works which were so fundamental and to which he had consecrated his effort and his spirit. They began to take away the machines, but foreseeing the worst, Stephen had sought to safeguard at least some of the smaller machines by giving them to past pupils. After abandoning the locale, even the oratory could not continue and the Salesian work was restricted to running the parish. The Ràkospalota chronicle notes that on December 19, 1949: “We completely abandoned the old Clarisseum and are in the same area, near the former print shop. We have adjusted as best we can but there is very little room… Besides the print shop, naturally, the bookstore was also expropriated and this has meant even greater reduction in available space.”

A government decree established that from January 1, 1950, teachers of Religion had to be paid by those who sent their children to the lessons. This was another manoeuvre to eliminate the already greatly reduced religious instruction in the schools.

The Fateful 1950

In June 1950 the Communist government declared all Religious Orders and Congregations suppressed, in Hungary. Beginning on June 7, deportation of Religious began, and they were interned in concentration camps (generally in old monasteries). The Salesians, too, were dispersed; some were brought to the concentration camps; the young Salesians and novices returned to their families, or to their relatives. The Salesians at Ràkospalota received the order to abandon even the hovels in which they were holed up. The Superior of the Salesians in Hungary, Fr Vincent Sellye, was arrested near the Austrian border, imprisoned in Budapest, accused of having tried to leave the country; he was condemned to two and a half years of imprisonment.

On August 30, the government and the President of the Hungarian Bishops’ Conference signed an “accord,” on the basis of which, in exchange for “backing” the political government, in September the Religious interned in the concentration camps would be released. But, a short while after the accord, on September 7, the State authorities withdrew permission to work for anyone from Orders and Congregations in Hungary; practically speaking, this meant the dissolution of Communities and the nationalization of their goods. Only a very reduced number of Religious, under many restrictions, remained functioning in eight high schools restored after two years of interruption (from 1948): two for the Benedictines, two for the Scolopians, two for the Franciscans, and two for girls to a local feminine Congregation.

The Salesians lost everything: the buildings were occupied by the State. The Religious were dispersed and each one had to find some type of work to survive. Some worked as organists, some as sacristans, others did various kinds of manual work; still others were taken in by the Diocese and sent to small country parishes. They could not reside in the city, nor maintain contact among themselves and, for a long time, were placed under police surveillance. The poor Provincial, Fr Sellye, on trial for a second time, was condemned to 33 years in prison.

Stephen remained for as long as possible in Ràkospalota, in whatever lodging he could find, and continued to keep contact with the young in his groups. But afterwards, in order to survive, he had to retire for a time to Szolnok, to his family, and to seek work in a print shop. Not only his technical talents, but as an educator and leader among the young shone forth. For this reason he was recalled by the local administration to Budapest to take charge of a group of orphans gathered by the Communist Party. Still, he continued his work as catechist clandestinely, in various ways. Even in the group of orphans he developed his gifts as a Christian educator, well aware of the risks he ran. Some of these young people were chosen to form part of a special police corps at the orders of the dictator Ràkosi, but they remained faithful in their hearts to the values of Christian ethics which had been inculcated in them by their leader.

At a certain moment in 1951, realizing that he had fallen into suspicion with the political police, Stephen changed his last name and place of residence and found work in a Persil (detergent) factory, but all the while continuing his clandestine apostolate among the young. Seeing that the police were keeping a close watch on this confrere and his Superiors, with whom he was keeping covert contact, they wanted to get him out of the country. When everything was in readiness for him to cross over the border into Austria Stephen did not wish to take advantage of the opportunity but decided to remain in Hungary. He thought that it was not just for him to leave, when the young whom he was following were running the same risk of being discovered and condemned. For him, it would have been running away from his responsibilities as a Christian educator.

He then chose to change his residence a number of times. Finally, he remained in Budapest, having accepted to share his lodging with a young confrere, Tibor Dàniel, who, at the time of the dispersion, was studying Theology. This little apartment became the center of his clandestine apostolic activity. Here, as also in various places around the capital, he continued his work of formation. It often happened that he received letters from the young people he was following. His correspondence certainly contained no allusion to politics, much less any idea of a plot, of which he was later accused. He only gave answers and advice regarding Christian spiritual life, which the young people wanted to deepen. The atheist regime, however, fearing anything that was Christian, used spies to keep an eye on all the citizens, but followed the activities of the dispersed religious with particular attention. Above all, it was of great importance to the regime to keep a close watch on the young, who were the nerve centre of the system. Bear in mind that even at Easter 1989 (the vigil of the fall of the Communist regime!), the agents of the AEH (Allami Egyhazugyi Hìvatal = the State Office for Ecclesiastical Affairs) presented their report on State workers, above all the teachers, who were present at Easter Mass. They sought to keep the Church far away from the young at all costs – especially the workers – the propagandist base of the Party. It was considered a capital crime to gather youth for religious formation. Immediately accusations of plots or conspiracies against the State rained down and this carried with it severe penalties, especially during the 50s, under the dictatorship of Matyas Ràkosi. It is against this background that we must place the activities of Stephen.

Arrest and Sentence

Right where Sandor and Daniel lived there was a dangerous situation. The woman who owned the building had a husband who worked for the infamous AVO (political police). Noting Sandor’s substantial correspondence, she began to open his letters using varied methods learned from her husband. The contents were passed on to the police who had both the recipient of these letters and his roommate under watch.

Something happened then and to understood it, it needs to be put in the context of something the regime was doing. We take it from an expert on the events of the era: “When the Communist Secret Police enlarged its ranks in 1949 to 30,000 members, they looked at orphaned youth and workers as “the most trustworthy of quarters” from which to dig up and form good Communist police. After a formation period of three months they trained the best as “Guards of the Party.” These received the rank of subaltern or officer and their task was to protect/defend the principal heads of the Party – the Party of the Hungarian Workers, as it was then called – Ràkosi e Géro. They recruited Albert Zana and some of his companions (past pupils of the Clarisseum, who had been followed up by Stephen) first as military and then in the Secret Police (AVO). These young police officials, even following the nationalization of the Institute of Ràkospalota and the expulsion of the Salesians, kept up their relationship with their teachers. Stephen Sándor used to meet regularly with his past pupils and some of their friends at the Clarisseum or in private apartments. Among themselves they prepared to resist the atheist propaganda of the dictatorship and even helped others to remain firm in the Faith. Even these young police officers brought friends to the Faith.

Involuntarily though they committed a “mistake.” In those days, on the main road from Ujpest, a new pub had been opened by the name of “Hell’s Tavern.” On the side of the entrance there was a sign which read: “Entry to Hell.” These young men considered it to be a way of making fun of religion. (This is an indication of the religious sensitivity of the time; today it would be almost unimaginable.) On the following morning, the young men sprayed tar over the writing. The owners of the place told AVO and their police dogs led them to the Clarisseum. Here they captured Hegedus Hajnal, then a fifteen-year-old student at the high school, who was arriving just at that moment. Using torture, they got out of him the names of the other members of the group and the name of their Religious leaders. Even in the Party there were members with good intentions. As soon as the arrest order was issued, they alerted Stephen about what had happened. The Salesian Superior, Adam Laszlo, as we already mentioned, had foreseen the possible need to get his confrere out of the country clandestinely, but Stephen felt he could not run while his disciples found themselves in danger in their country. He said to his friends that he was ready even for martyrdom. But the owner of Daniel’s house had Stephen, Daniel, and other Salesians imprisoned. Within a short time they also imprisoned the other young people who had been implicated. Matyas Rakosi (the Dictator) decided on an immediate sentencing of the young officers.

Later, a few details of the arrest came to light. On the morning of July 28, 1952 the political police showed up at the lodging and arrested Stephen. They then awaited Tibor Daniel’s return, in the afternoon. When he entered into the room, he was welcomed with a brutal slap. They brought him to the main police station, the infamous building at 60 Via Andrassy (today known as the “Museum of Terror”), where he underwent repeated torture which ruined his liver and spleen. Finally, in order to avoid making a martyr of him, they released him in extreme condition, in his village Asvànyràrò (in the north, near the Slovakian border). A little while later, as a result of the torture to which he had been subjected, he died in the arms of his mother and of his sister Elizabeth.

As for Stephen, he was brought to the Military Tribunal prison in Budapest (in the region called Buda, Fo Utca), where he endured beatings and continuous lengthy interrogations. The authority for the trial fell to the Military Tribunal inasmuch as there were members of the armed forces among the accused. On account of the inhuman torture and the sadly all too well-known procedures used on “political” prisoners of the time (cf. Cardinal Mindszenty), Stephen was forced to admit to “crimes” which would implicate him, well knowing that such a declaration would have constituted a motive for the military tribunal to condemn him to death.

The trial began on October 28, 1952. Sixteen charged were present: nine had served in the special Police Corps; five were Salesians; and two were young students, one male and one female. All proceeded behind closed doors and in one hearing only. It was, as usual, a farce with everything already decided. Lieutenant Colonel Béla Kovàcs presided over this mock trial in which the final decision had already been made. He was assisted by two lieutenants of the AVH (Secret Police). The State Prosecutor Major Gyorgy Béres represented the personal expression of Dictator Rakosi. The court immediately declared verdict number I/0308/1952: the death penalty for Stephen and for three young officers, who were retained “guilty of plotting against the people’s democracy and of high treason.” Two days later a request for pardon which had been presented as a matter of procedure was turned down.

Behind the veneer of the trial, the wrath of the regime in the face of the Religious who kept up their relationship with young workers was obvious, for the young were considered to be potentially the hard core of the dictatorship.

During the years of the Communist regime, some thousands of young people, fully aware of the risks they were taking, kept attending the clandestine Catholic youth groups in every way they could, and with the excuse of going on outings or having family parties, were part of religious formation encounters and retreats. Many of them were imprisoned and tortured. Many were excluded from attending high school and university and had to take up manual labour jobs immediately.

In Military Prison at Fo Utca

Still today, whoever visits the Hungarian capital, in the region of Buda, and travels along Main Street (which is what “Fo Utca” means), is struck by the gloomy, imposing nature of the Military Tribunal, constructed completely of dark stone. The upper stories housed the military prison. Cell number 32 in the “High Treason” section was where Stephen was from the day of his imprisonment until the night of June 8, 1953.

We have some information about these ten and a half months from some cellmates of his who survived. Here is one such testimony: “During the weeks I spent in the common cell we did everything we could to live a spiritual life, in the noblest sense of the word… We prayed together and recited the Rosary secretly, because even among our cellmates there was a certain internal surveillance. Every cell had its “commandant” who was responsible for observing and reporting on any irregularity, which then did not go unpunished. (The regime purposely planted someone who would be a fake prisoner and tried to gain the confidence of the prisoners). Our friend Stephen tried to give courage to his companions through consoling prayers and spiritual thoughts.” Despite the fact that he was aware of his tragic destiny, he brought calm for other prisoners.

A Priest, Jòzsef Szabò, a prison companion, confirmed: “We knew that Stephen was ready for martyrdom. He was aware that from the place in which he found himself there was only one way out, the one that brought him to the gallows. It was understandable that, like everyone else, he too was attached to life and nurtured the hope that he would survive, but he didn’t give any sign of wanting to shrink to the level of compromise. He told me, his spiritual father, in confidence and with the greatest sincerity during our conversations in the cell that he had never participated in any political plot. I never noticed any political interest on his part… I remember that there were more than fifty of us in the cell. We were unable to speak freely among ourselves; everyone was part of an assigned group in which there were spies. Being in such a desperate situation, all of us were placed under severe sentences. The lightest penalty consisted in a 15-year imprisonment; but life sentences or death penalties were numerous. In such a situation, people were very open to spiritual thoughts under the form of spontaneous preaching. I spoke of eternal truths to the group; Stephen Sándor also did the same… We prayed the entire rosary, counting on our fingers. We saw how much comfort saying prayers gave those condemned to death. Stephen often asked me to go to our prison companions to hear their confessions and to give them absolution… Those condemned to death sought spiritual comfort from him.”

One of his former companions from school, Mihàly Szantò, high up in the Party, tried to convince Stephen to cooperate with them. They knew, in fact, of his abilities and above all of the influence he exerted over the youth. But he never gave in. His cellmates who survived were all unanimous: even after receiving the death penalty, he comforted the others in the cell. At times of severe hunger, he shared his food – which was already little – with them.

June 8, 1953: the Supreme Witness

After the official communication of his death sentence, he was transferred from cell 32 to the upper floor of the military prison, to the cell for those condemned to death, to await execution. A surviving cellmate confessed that he still had fixed in his memory, fifty years later, the sorrowful scene when the prison guards came to cell 32 to take away his personal effects: a little toothbrush, a comb, and a towel. For the prisoners, this was the sign that the person concerned had been transferred to the cell with those who would go directly to their execution.

The survivors affirmed that it was impossible to know exactly where they held the executions. In general, at least until 1953, they were carried out in the courtyard of the prison itself. In order to drown out the screams of the condemned, they used to rev up the engine of the truck they used as a platform. When this sinister noise was heard in the cells, they understood that they were executing one of the condemned, especially by hanging. Stephen was the second one to be hanged, as we understand from the records.

His corpse, together with those of the others who were put to death with him, was brought by truck to the cemetery of the judiciary prison in the town of Vàc where they were buried all together in a common grave, without any signs of identification. Despite several searches on the part of his family and the Salesians, they still did not succeed in finding his burial place. On the other hand, the corpses that were exhumed afterwards after the fall of the regime, presented so many signs of torture that their identification was made very difficult. But whoever has the gift of faith knows also that the martyred body of Stephen is awaiting the glorious day of the Resurrection.

Reputation of Martyrdom

In 1989 the Berlin Wall fell and the Iron Curtain came down. In 1990 free political elections were held in Hungary and the new Parliament approved the law of freedom of conscience and religious freedom. Little by little they began to reconstruct the Religious Communities which had been abolished in 1950. Even the few remaining Salesians began to establish some communities in the few places restored to them by the Government.

A few years needed to pass before the sons of Don Bosco could reach a sufficient number of available personnel so as to be able to take care of gathering documentation and begin, in 2006, the canonical process for the recognition of Stephen’s martyrdom. On December 10, 2007, the Diocesan Process was closed in Budapest and word was sent to Rome, to the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints.

In the meantime, the people of God had become aware of the tragic happenings and of the heroic conduct of so many Christians in Hungary, under the toughest Communist regime. At an official level, and even on the level of the common person, many events which before were only supposed or barely whispered about, have now come to full light. Some survivors, who at first were forced to keep silent, have now contributed in helping reconstruct, at least in part, the true facts. In our case, for example a parish priest, Fr Jòzsef Szabò, explained to his faithful people that, having himself been a cellmate of Stephen, he knew very well that he was killed because of his faith which led him to carry out an intense pastoral activity in youth groups. He is a martyr who is a model of youth ministry which springs from an intense relationship with God, is lived in profound simplicity and spontaneity, so far from every form of external bigotry, and solidly anchored in constant motivations of faith, and concerned, besides, with giving the young that love of Jesus which he felt for them.

Many people can see how much good can be done, particularly for the young, through an official recognition of this young man’s martyrdom. He is an example of a life well-lived, nurtured on essentials which, when contrasted with the instability of today, is timely and urges us to question ourselves on the way we live, on the true motivations behind the way we act. Being faced with the motivations that guided the martyr to confront and overcome so many sufferings unjustly inflicted upon him, urges us to review our situation in God’s eyes. In a particular way, it is an encouragement to reflection for those who must work in one way or another with the young in difficult times, as are ours, too, though in a different way. The cause to which he dedicated his entire life, the formation of a Christian sensitivity in the youth’s world of work, is still as timely as ever.

Those who knew him testified that his exemplary conduct was not an occasional attitude but the fruit of a conviction that constantly sustained it. His martyrdom was but the consistent conclusion of an entire life of simple faith and profound love for the young, always filled with trusting hope, even in unfavourable circumstances. This is the attitude that St. John Bosco inspired in his sons: “I will give my life for the young until my very last breath.