Undocumented child graves in Canadian boarding school

Two articles offering alternative views on a tragedy in Canada. Both need to be read for a balanced view!

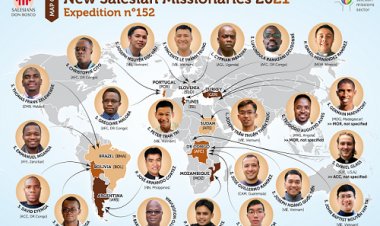

Two articles offering alternative views on a tragedy in Canada. Both need to be read for a balanced view! And this raises questions about thousands of other undocumented graves in many other institutions around the world, and especially on our continent of Africa. Thus the importance of maintening records!

When Your Church Hides Dead Children - Adam A.J. DeVille - June 9, 2021

My church and my country, and a community I value, have been implicated in hiding a mass grave of abused children. An unmarked mass grave of 215 indigenous children has been discovered under a residential school in British Columbia run by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. This has haunted me as a Catholic, as a graduate of an Oblate institution, and as a Canadian.

We have not done well. We are not doing well. The statement from the president of the Canadian Catholic bishops said too little.

This dark and dolorous news from the former Kamloops residential school in British Columbia ensnares all Catholics. It affects the families especially, for clinical evidence indicates that trauma is transmitted trans-generationally.

Many Catholics may not see that, may not want to see that. We don’t want to feel responsible for things our ancestors (family or ecclesial) did. Western individualism has infected the Catholic imagination for a long time now, leading many of us to shrug at this news and move on, thinking it has little to do with Catholics in the United States and England — after all, it was more than a century ago in another country, and everyone involved is long dead.

Anglicans Better Than Catholics

As an Anglican in 1993, I was grateful to the then-primate, Archbishop Michael Peers, for his apology to native peoples for the abuse they received at the hands of the Anglican Church of Canada. This was then followed by the ACC restructuring itself to give aboriginal Anglicans much greater autonomy and self-governance to foreclose future possibilities for abuse.

Catholic leaders have, in Canada and elsewhere, been more stingy with their apologies. Indeed, in this same time certain American Catholics, led by Richard John Neuhaus and Avery Dulles and other prominent Catholic academics, argued that Pope John Paul II should not offer a global apology prior to entering the third millennium. Fr Neuhaus seemed most concerned that many would misinterpret the apology and the Church would look bad.

Wisely, the pope ignored these critics and went ahead with a singular liturgy on the first Sunday of Lent in 2000 (the “Day of Pardon”). He preceded it with a careful and important theological reflection.

Our Individualism

Our individualism feeds off and also encourages an even more widespread notion, namely that we cannot judge the past but only “understand” or “contextualize” it.

The idea of moral neutrality is a disguise designed to deceive. Some claim the pose of “neutrality” and ostentatiously refrain from “moral judgments” about the past. Instead, they insist with studied vagueness that everything must be seen “in context” (a term no one really thinks about). Or they employ “dis-attribution” and other dodges. They say, for example, that “bodies were discovered,” as a way of not saying whose bodies they are and why they were buried and who killed them.

Catholics should not dodge this deadly discovery of 215 dead children. We claim to live by the standards, by commandments, of an eternal and unchanging truth that does not shy away from denouncing evil, both past and present. And so, we must judge this news rightly as evil, as a terrible abomination in the sight of the Lord, as a great sin crying out to heaven for vengeance.

In Reconciliatio et Paenitentia, the late pope rightly recognized that “One can speak of a communion of sin, whereby a soul that lowers itself through sin drags down with itself the Church and, in some way, the whole world.”

In other words, “there is no sin, not even the most intimate and secret one, the most strictly individual one, that exclusively concerns the person committing it. With greater or lesser violence, with greater or lesser harm, every sin has repercussions on the entire ecclesial body and the whole human family.”

What Do We Do? Denunciations are only the beginning. What else must we do? Clinically now-standard practice in treating trauma recommends we do three things:

create a place to tell this story in safety;

tell it;

and then and only then gradually move on from it.

The best place to tell the story is in the liturgy, which is itself a larger narrative of trauma (torture, false arrest, unjust execution of an innocent man) capacious enough to hold all our dolours while gently directing them and us to the final triumph over wickedness, sorrow, and pain in the resurrection.

Let us, from henceforth, keep this date of discovery of these dead children in our liturgical calendars as a day of fasting, penance, and mourning; let us don our dark vestments, deny ourselves festal foods, and lament these losses. Let this day become another “Holy Innocents” memorial in the sanctoral cycle of every year.

Let us write new propers for this day; let us read the psalms of lament; and let us, led by bishops and members of the Oblate community, kneel in public penance as the names of these children (if they can be discovered) are read aloud in a new litany of saints and martyrs.

Then let the longer, wider story of residential schools continue to be told, with this new chapter added to the existing history.

Finally, as this is happening, the Catholic church in Canada and elsewhere must seek genuine structural reforms to every aspect of her life so that never again can such abuses be committed or covered up.

Healing Memories

Only if all this is done will we have any chance of healing the memories of aboriginal Catholics and all who have suffered, and continue to suffer, abuse in the Church, and from the Church. The healing of memories we need now is not just a pastoral phrase tossed off by some pope in a burst of ecumenical goodwill decades ago.

The healing of memories is a lifelong task for Catholics, as St. Augustine of Hippo long ago recognized: “The entire task in this life, dear brothers, consists in healing the eyes of the heart so that we may be able to see God.”

Let us get to work at once, and for as long as it takes. For the human heart finds it nearly impossible to see the face of God in a mass grave of innocents. If we do not confess and repair this evil, each of us, as the Lord warned, may merit having a “great millstone fastened round his neck and to be drowned in the depth of the sea.”

- Published in the Newsletter @catholicherald.co.uk

- Adam A. J. DeVille is associate professor in the theology-philosophy department of the University of Saint Francis in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

A second report and viewpoint follows below...

*************************************************************************************

The discovery of undocumented child graves in Canadian residential school run by the church, requires further explanation!

The sad discovery of 215 unmarked child graves found at the Kamloops Indian Residential School has led to much sorrow and outrage, as well as stinging attacks against the Catholic Church. But the blame is to be shared by the Canadian Government itself for its historical policies.

Despite the universal condemnation, numerous questions still remain regarding the case. Canadian author Michael O’Brien, himself a former pupil at one of the residential schools, has warned of the danger of accusing the Church of murder before any real information is known about the recently discovered graves, including the context of the residential school period.

Chief Rosanne Casimir from the Tk’emlups te Secwépemc First Nation, revealed May 28 that the bodies of 215 schoolchildren, some aged only three years old, had been discovered underground through the use of ground penetrating radar. Casimir mentioned that there had been a “knowing in our community” which led to the search and discovery of the bodies.

Casimir also noted that “these missing children are undocumented deaths,” adding that many questions remained to be answered, and also hinting at the possibility of finding more bodies pending further investigation. She described it as an “unthinkable loss that was spoken about but never documented at the Kamloops Indian Residential School.”

Casimir noted that the investigation had been ongoing since the early 2000s, stating that stories from former pupils had fuelled the desire to search for graves.

Residential school system

Kamloops residential school, located in southern British Columbia, was run by the Catholic Church from 1890 to 1969, at which point the federal government took over the running of the facility and turned it into a day school until its closure in 1978. At its height, Kamloops had over 500 children enrolled during the 1950s and was once the largest school of the residential system.

The school was given to the guidance of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in 1893, by order of the government. However, by 1910, the principal reported that the government was not providing sufficient funding to properly feed the children. A similar report was made in the 1920s.

In 1924, the building was partly destroyed by fire.

It was part of the nation-wide residential school system in Canada, which saw indigenous children unjustly removed from their families, and taken to the schools for the supposed purpose of education and assimilation into the non-indigenous culture. The schools were largely run by the Catholic Church, although by no means were they exclusively under Catholic care only, as other Christian denominations also ran some of the schools.

The seized children were prevented from speaking their native tongue or from engaging in their cultural practices from home. Once attendance at the schools became mandatory in the 1920s, children were forcibly removed from their families and parents threatened with prison if they did not comply. Upon arrival at the school, children rarely saw their families, with many disappearing or never seeing their families again.

The residential school system finished with the closure of the last school in 1996. Reports suggest that over 150,000 children attended the schools during their operation.

Accounts of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse were widespread within the schools. As regards Kamloops, a former employee of Kamloops, Gerald Moran, was convicted in 2004 of 12 counts of sexual abuse and given three years in jail.

The National Truth and Reconciliation Commission was subsequently established due to a legal settlement between the Residential Schools Survivors, the Assembly of First Nations, Inuit representatives, and the federal government and church bodies. A lengthy report by the Commission released in 2015 interviewed many thousands of witnesses, including numerous former students at the schools, and revealed that the Indigenous children who attended the schools died at a higher rate than school aged children in the general population.

The report noted 3,200 students who died while attending the schools, although the New York Times recently reported the number to be at least 4,100. Causes for these deaths ranged from neglect, disease, accident, or mistreatment.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation has documented records for 51 children who died at Kamloops, between 1900 and 1971, although this number is far short of the 215 recently discovered bodies.

Kamloops and the Catholic Church

In the wake of the recent discovery of the unmarked graves, numerous high-profile figures have attacked the Catholic Church, with calls for accountability and desires for amends to be made coming from all levels of society. Accusations of murder and genocide have been levied against the Church since the discovery.

In a recent televised address, pro-abortion Prime Minister Justin Trudeau slammed the Catholic Church for its role in Kamloops and the wider school system: “Make it clear that we expect the Church to step up and take responsibility for its role in this and be there to help in the grieving and the healing, including with records that is necessary. It’s something we are all still waiting for the Catholic Church to do.”

Trudeau formerly attacked Pope Francis some years ago, when the Pope did not personally apologize for the role the Church had played in the residential school system.

The Catholic hierarchy have come out in the last few days with statements of sorrow and sympathy. Pope Francis spoke at the Sunday Angelus, saying he “joins the Canadian Bishops and the whole Catholic Church in Canada in expressing his closeness to the Canadian people, who have been traumatised by the shocking news.”

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops issued its own statement, writing to “pledge to continue walking side by side with Indigenous Peoples in the present, seeking greater healing and reconciliation for the future.”

Edmonton’s Archbishop Smith also expressed his “deep regret and profound condolences,” to the families of the children, recalling his own apologies made to the Truth and Reconciliation commission.

He was supported by Vancouver’s Archbishop Michael Miller, who talked of the “ongoing need to bring to light every tragic situation that occurred in residential schools run by the Church. The passage of time does not erase the suffering that touches the Indigenous communities affected, and we pledge to do whatever we can to heal that suffering.”

Michael O’Brien warns against hasty judgements

In the wake of this sudden surge of anti-Catholic rhetoric, based on the tragic, but as yet unexplained, discovery of the unmarked graves, LifeSite spoke at length with well-known Canadian Catholic author Michael O’Brien, who spent three years in one of the residential schools himself. O’Brien later gave testimony to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission during the many hearings conducted in order to draw up the final report.

O’Brien cautioned against using the recent news as a launchpad from which to attack the Catholic Church.

O’Brien revealed that he had indeed witnessed abuse while at the school, although from lay employees in the schools, and not from the clergy or religious sisters.

He pointed also to the chief underlying issue of the institutional abuse of children being removed from their families by the state authorities, and then taken to the schools, noting the “long-term psychological and social effects of this.”

But in the specific case of the Kamloops school, he re-issued the call for caution. “Where are the known facts to date?” he asked. “At this point there is only innuendo and insinuation.”

Kamloops graves in context: Infant mortality rates

Indeed, his warning is well-founded. While Chief Casimir mentioned existing rumors of unmarked graves, there was no explanation for why they might be there. Any number of causes for the children’s deaths could be offered, and accusations and explanations of the bodies can only be factually supported following forensic examinations.

Another point O’Brien raised was the seeming lack of investigation into mortality records during Kamloops’ operational years, to determine the expected level of child deaths which would be normal for the period. Some statistics show that for infant mortality (i.e. deaths under the age of one year), the rate was 187 deaths per 1,000 births in 1900. High death rates were seen also between 1910 through 1920, coinciding with the Spanish Influenza epidemic.

In an age marked by such high child mortality, and in a school which was the largest of its kind, such a number might not be unexpected in its 80-year lifespan; however, questions remain about why these 215 deaths don’t appear in official records.

Meanwhile mortality rates for children under the age of five record 296.75 deaths per 1,000 births in 1900. That figure only dropped beneath 100 deaths per 1,000 births in 1935, with high rates of child mortality consistently seen from 1910 through 1920.

“Any discussion of death in childhood and the experience of children and families living with life-threatening medical problems has to be put in the context of child health as it has improved during the last century,” wrote the National Centre for Biotechnology Information. As an example of this change in demographic mortality, in 1900, 30% of all deaths in the U.S were of children aged less than five years old, compared to just 1.9% in 1999.

In fact, such was the concern about Canada’s national infant mortality that Ontario politician Newton Rowell raised the matter before the House of Commons in 1919. Indeed, the First Nations people themselves have historically been noted to be less resilient against infectious diseases, such as influenza epidemics, measles, and smallpox.

O’Brien also called for an examination to be made about the graves and the number of bodies found. Official records account for 51 children, and with the latest discovery some 266 children are known to have died or be buried at the school. In an age marked by such high child mortality, and in a school, which was the largest of its kind, such a number might not be unexpected in its 80-year lifespan; however, questions remain about why these 215 deaths don’t appear in official records.

‘Department of Indian Affairs refused to ship home the bodies of children for cost reasons’

O’Brien noted that transportation difficulties abounded during Kamloops operational years. This meant that the bodies of children who died, for whatever cause, very often could not be returned to their families and were thus buried on the school premises. He was supported in this by the National Post, who noted how the government’s “Department of Indian Affairs refused to ship home the bodies of children for cost reasons.”

Upon arrival at the school, the seized children rarely saw their families, with many disappearing or never seeing their families again. If they died, the government’s Department of Indian Affairs often ‘refused to ship home the bodies of children for cost reasons.’

In fact, the National Post wrote that unmarked graves were not uncommon in the residential schools, saying that it was “never a secret that the sites of Indian Residential Schools abounded with the graves of dead children.”

The graveyards of the schools were sometimes used by locals even after the school had closed, although the more regular occurrence was for the cemeteries to become overgrown, damaged by prairie fires, and the wooden grave markers destroyed over time.

‘Until more facts are known, we are left only with insinuations’

Upon further investigation into the context of the residential schools, the recent discovery of the 215 unmarked graves presents society without any conclusions, other than the mere physical presence of the graves.

Without forensic evidence, nor any bodies even having been exhumed, nothing can be postulated about how the children died, or when. Given the high mortality rate generally, alongside the even higher mortality rate of the First Nations people, higher rates of child mortality – and the accompanying graves – are to be more expected in the time of residential schools compared to today.

O’Brien’s warnings have been supported by the National Post, which noted the manner in which graves easily fell into ruin over time, and through external forces such as the ravages of nature, or land development.

While the residential schools undeniably caused great harm in multitudinous ways, as often harrowingly described in a limited manner by the Truth and Reconciliation Report and as evidenced by the government’s undermining of parental rights of First Nation parents, care must be taken not to use the discovery of the 215 graves as a means to blindly attack the Church without any supporting evidence.

The schools, financed by the state and run by a variety of churches, not merely the Catholic Church, remain a dark period in Canada’s history. However, O’Brien warned against “projecting onto the past our consciousness of the present.”

“Until more facts are known, we are left only with insinuations,” he explained.

- Michael Haynes - KAMLOOPS, British Colombia, June 9, 2021 – on LSN