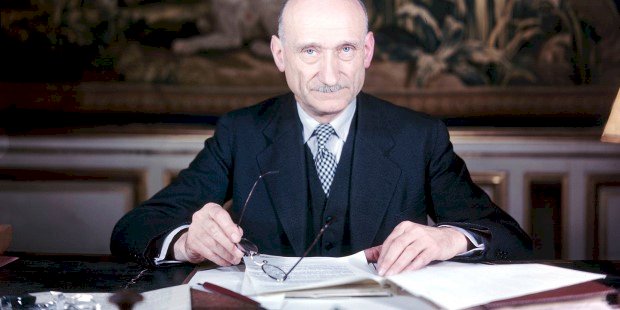

Robert Schuman (1886-1963)

Architect of modern Europe - politician on path to sainthood

Robert Schuman (1886-1963) - Architect of modern Europe - politician on path to sainthood

by Sebastian Milbank

Pope Francis has authorised a decree advancing the cause of canonisation for Robert Schuman, recognising the “heroic virtues” of the 20th century French statesman instrumental in Europe’s post-war settlement. Schuman’s vision of a Europe united across national boundaries began where his life began, in Luxembourg, where he was born in 1886 to a Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Schuman, who had left for Luxembourg following Alsace-Lorraine’s annexation by Germany, and to native Luxembourgian, Eugénie Suzanne Duren.

Educated in law, economics, political philosophy, theology and statistics in several German universities, Schumann exchanged his German citizenship for French citizenship when Alsace-Lorraine was returned to French rule. His legal abilities, and his grasp of German and French law and culture, became apparent as a he rapidly rose in Lorraine’s regional politics, and harmonised the region’s German influenced law with French civil law, the results of which were dubbed the “lex-Schuman” by contemporaries.

After France’s surrender, Schuman briefly accepted a role in General Pétain’s government in Vichy as minister for refugees (a position he had held under the previous government), but soon resigned his position, and following open protests against the methods of the German occupation, was arrested by the Gestapo. He narrowly avoided being sent to Dachau concentration camp, and having escaped from detention, he spent the rest of the war in hiding, sheltering in a number of convents and monasteries.

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany, Schuman was rocketed into prominence, serving as Prime Minister under de Gaulle, and taking the first steps towards the Council of Europe and the single market of the European Community. In 1950, whilst serving as foreign minister, he advanced the Schuman Declaration, which integrated the German and French coal and steel markets, and laid the framework for what would later become the European Community and then the European Union. He was also instrumental in the setting up of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), as well as having a tremendous role in stabilising France’s post-war politics and economy.

Schuman’s secular sainthood has long been affirmed, but the deep Catholicity of his politics and policies have often been forgotten or overlooked. In his personal life Robert Schuman was an intensely devout Catholic, a daily communicant, and immersing himself in a life of prayer and study of the Bible, remaining celibate all his life.

An admirer of Aquinas, Pius XII and Jacques Maritain, he applied the principles of Christian democracy to his politics, and sought a vision of a united Europe that reflected both modern democratic values, and the ancient unity of Christendom that harked back to the age of Charlemagne.

Speaking in 1949, at the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community, he said:

“We are carrying out a great experiment, the fulfilment of the same recurrent dream that for ten centuries has revisited the peoples of Europe: creating between them an organisation putting an end to war and guaranteeing an eternal peace… The Roman church of the Middle Ages failed finally in its attempts that were inspired by humane and human preoccupations. Another idea, that of a world empire constituted under the auspices of German emperors was less disinterested; it already relied on the unacceptable pretensions of a ‘Führertum’ (domination by dictatorship) whose ‘charms’ we have all experienced… Audacious minds, such as Dante, Erasmus, Abbé de St-Pierre, Rousseau, Kant and Proudhon, had created in the abstract the framework for systems that were both ingenious and generous. The title of one of these systems became the synonym of all that is impractical: Utopia, itself a work of genius, written by Thomas More, the Chancellor of Henry VIII, King of England… The European spirit signifies being conscious of belonging to a cultural family and to have a willingness to serve that community in the spirit of total mutuality, without any hidden motives of hegemony or the selfish exploitation of others. The 19th century saw feudal ideas being opposed and, with the rise of a national spirit, nationalities asserting themselves. Our century, that has witnessed the catastrophes resulting in the unending clash of nationalities and nationalisms, must attempt and succeed in reconciling nations in a supranational association. This would safeguard the diversities and aspirations of each nation while coordinating them in the same manner as the regions are coordinated within the unity of the nation.”

With arguments still ongoing over the future of the European Union, Britain’s ongoing relationship with Europe and the status of Northern Ireland, the timing of the decision to advance Schuman’s cause is a clear symbolic affirmation of the centrality of European peace and unity for Pope Francis. This follows the Pope’s words in May of last year, on the 70th anniversary of the Schuman Declaration, which, according to Pope Francis, “inspired the process of European integration, enabling the reconciliation of the peoples of the continent after the Second World War, and the long period of stability and peace from which we benefit today”.

It might also, at a time when secularisation has spread across Europe, and the Church is clashing with many European governments over issues of bioethics, refugees, and ecology, serve as a reminder of the essentially and necessarily Christian nature of Europe, a view that Schuman continually emphasised.

As he said of the European Community in 1958:

“We are called to consider ourselves of the Christian basics of Europe by forming a democratic model of governance which through reconciliation develops into a ‘community of peoples’ in freedom, equality, solidarity and peace and which is deeply rooted in Christian basic values.”

- Published in the Tablet – June 2021